Banish your food demons and stay binge-free!

Jane is a 24-year-old student. She is quite happy with her life, achieves well in academics and has a good circle of friends. However, about a year ago her relationship ended and sometimes she still becomes overwhelmed by sadness and loneliness. More and more often she treats herself to huge food rewards when getting home after a long day, only to spend the rest of the evening seeking for more. She feels powerless to control her cravings and unable to stop eating even when totally full. She is then flooded with feelings of regret and guilt for once more ruining her diet and worries that she will never get rid of the extra weight she recently gained. Following her nutritionist’s advice, Jane started seeing a psychologist and is now being treated for binge eating disorder.

WhAt is Binge EAting Disorder?

Since 2013, Binge Eating Disorder (or BED) has been recognized as a distinct eating disorder, according to the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the handbook used by health care professionals worldwide as the guide to the diagnosis, research and treatment of mental disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

How can you learn to recognize BED? Well, incidents of binge-eating might involve eating very large amounts of food (usually unhealthy) without being actually hungry; eating much more food than most would eat in a similar time period (e.g. within 2 hours) or situation; eating unusually fast and up to the point of feeling uncomfortably or even painfully full. Most importantly, during these episodes the person feels that they have little or no control over how much they are eating and often report that “eating takes on a life of its own” and “once they start eating there’s no stopping”. Binge-eaters often feel disgusted, guilty and ashamed of themselves, their eating habits, weight and body shape. They usually prefer to eat in secrecy and might avoid going out in public due to extreme embarrassment.

One thing all eating disorders have in common is that they seriously disrupt eating behaviors. Although binge-eating can occur in almost all eating disorders, what differentiates BED is that no actions are taken to undo or make up for the effects of bingeing like forced vomiting, fasting, taking laxatives or over-exercising, which are typically seen in patients with bulimia- or anorexia nervosa. As you might expect, this can only be damaging to the body. Indeed, people living with BED run the risk of gaining excessive weight, becoming obese, developing diabetes, heart disease and many other life-threatening health complications over time (Guerdjikova, Mori, Casuto, & McElroy, 2017).

BED doesn’t discriminate on age, race or cultural background and is more common than you might think. In fact, in a survey across 14 countries almost 2% of people experienced BED. And although all eating disorders reserve our attention, BED was found to be more concerning and prevalent than bulimia- and anorexia nervosa combined, in virtually all countries. Most interestingly, BED strikes men and women more equally than other eating disorders tend to- of those diagnosed with BED, almost 40% were men (Kessler et al., 2013).

It’s not just overeAting!

Reading this you might think “I’ve been there” and wonder whether you are the only one who is sometimes compelled to lie on the couch with a bag of potato chips while watching a film, who feels incapable of resisting a freshly baked cake without feeling hungry, who reaches for the cookie jar after a romantic breakup or overeats during festive celebrations and buffet dinners…

The answer is you are not! We all have our moments and eat too much at times or feel so hungry that a regular meal cannot satisfy our appetite. But only some of us struggle with BED.

Binge-eating and overeating are two terms often used synonymously in casual discussions about eating and attitudes towards food- yet their differentiation is quite important if we want to draw a line between pathological and “normal” (over)eating behaviors.

For starters, when we talk about BED, overeating behaviors don’t just happen occasionally, but rather occur on a regular basis. How often is regular? According to the DSM-5, the episodes must occur at least once a week for 3 months before the behavior can be considered recurring and meet the criteria for a BED diagnosis. As we saw before, another characteristic of BED is a sense of loss of control during eating. But doesn’t eating more than 1.000 calories at a sitting or eating beyond satiety (as it usually happens with overeating) also suggest some lack of control?

To address this question, a group of researchers from Chicago, Illinois conducted a study aiming to investigate the key difference between types of eating with respect to loss of control. To do so, they compared two groups of obese adults with and without BED. The participants were asked to rate their feelings and levels of control over eating, every day before and after their meals, for a period of seven days. After accounting for the amount of food consumed and the negative emotions reported by the participants, the researchers found that across the two groups those with BED experienced more loss of control over eating. What these findings suggest is that binge-eating and general overeating are two very different experiences. While consumption of large amounts of food and negative feelings accompanying eating can be signs of BED, it is the loss of control that helps us recognize the presence of the disorder and deal with it in its tracks (Goldschmidt et al., 2012).

Although this study only focused on individuals with obesity, we should keep in mind that binge-eating doesn’t always show up on the scale. Underweight or normal weighting people might also engage in binge- eating and suffer from BED. Likewise, just because someone is overweight does not necessarily indicate she/he is binge-eating.

WhAt cAuses Binge EAting Disorder?

While the exact cause of BED is unknown, experts believe that an interplay between biological, psychosocial and environmental factors is responsible for why binge-eating occurs.

Twin and adoption studies have shown that BED can sometimes run in families. So, if any of your close relatives (like a parent or sibling) is currently affected or has a history of binge-eating, then you may as well have inherited a susceptibility to developing the condition (Bulik, Kleiman, & Yilmaz, 2016). Biological abnormalities might also lead to compulsive eating. For example, the hypothalamus (the part of your brain that monitors and controls appetite) may not be sending proper messages about when you feel hungry or completely full. Likewise, hormonal irregularities such as an increased sensitivity to dopamine (a hormone responsible for feelings of pleasure and reward) or low levels of serotonin (a hormone related to mood balance and digestion) can explain why some people have trouble controlling their cravings for food (Mathes, Brownley, Mo, & Bulik, 2009).

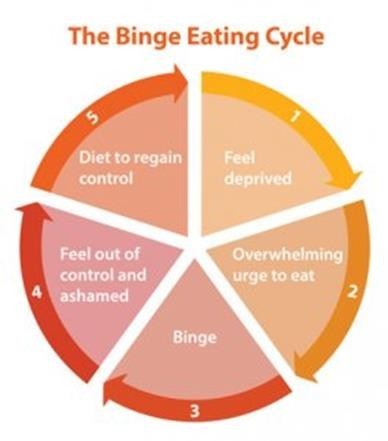

However, the answer isn’t that simple! So, before you start any digging into your genealogy book and blame it on your ‘bad’ genes, let’s have a look at some external factors that can increase your risk of developing BED. Scientists suggest that almost any type of traumatic or stressful life event from bullying and body shaming to childhood maltreatment and personal tragedies (e.g. deaths, separation) might potentially lead to food addiction and compulsive overeating, especially for those with genetic predispositions. You might not have seen this coming, but extensive dieting and food restriction can also have the same effect (Dakanalis et al., 2015; Mathes et al., 2009). How come you ask? You can think of it as a chain of events going somewhat like this: unrealistic ideals of beauty and societal pressures to be thin lead to body image concerns and low self-esteem, which in turn trigger hunger cues and binge-eating episodes. At this point, dieting may seem reasonable, but is not always possible. Before you know it, you are trapped in an eating circle with no exit signs. You have no clue about how to break free. How do you feel?

Probably even more deprived and distressed. And that’s not surprising. More than 80% of people suffering from BED also show signs of other psychological conditions such as depression and anxiety. This drove mental health researchers to take a closer look into the role that emotions might play in the onset and maintenance of the disorder. In a newly published research review, University of Maastricht (Netherlands)’s Karolien van den Akker and colleagues (2018) concluded that food cravings and emotional -compulsive overeating are learned behaviors that can be understood in terms of the ‘classical conditioning’ theory. This theory goes back to the 19th century when introduced for the first time by the famous physiologist Ivan Pavlov. To put it simply, classical conditioning is a form of learning via the process of association.

Let me give you an example. Milan is a 4-year-old boy visiting the doctor to get vaccinated. The doctor is kind and things go well at first, up until the moment when the needle pinches the boy’s arm. That’s really painful and little Milan immediately bursts into tears. Now, when Milan is 6, he goes in for a routine check-up. Just seeing the doctor approaching him, Milan feels distressed and starts crying. What happened there?

In ‘classical conditioning’ terms, when a neutral stimulus which initially produces no response (e.g. boy visiting the doctor) is repeatedly paired with a stimulus (let’s call this the ‘unconditioned stimulus’, e.g. vaccination) which automatically elicits a response (‘unconditioned response’, e.g. crying), it will eventually become a conditioned stimulus, or else, a “cue”. In other words, once the association between the two stimuli (i.e. the unconditioned and the conditioned one) is made, just presenting the conditioned stimulus is enough to evoke the same response. This new learned response is known as ‘conditioned’ response.

Now, let’s go back to our binge eating discussion. Unpleasant feelings including stress, loneliness, boredom and anger can become food-signaling cues (i.e. conditioned stimuli), if consistently paired with food consumption and a temporary attenuation of bad mood. Remember Jane? In her case, feeling sad and lonely was enough to trigger an uncontrollable episode of eating. Pretty much everything else (e.g. watching TV, socializing with friends) can become such a cue, if have been previously associated with food intake. In the long run, all these feelings/situations/contexts that make people tempted to reach for pleasurable food when not being physically hungry, become ‘wired’ to the brain and can eventually turn into a bad eating habit. Indeed, research has shown that emotional eating and food cravings are the most common antecedents of BED. The burning question is how can we ‘unlearn’ these eating behaviors and beat our food addiction.

The answer might be in cue exposure therapy (CET), a well-known behavioral intervention that uses the concept of classical conditioning to counteract learned behaviors. With repeated exposure to food-signaling cues and without engaging in addictive behavior (i.e. binge-eating), the cues start to lose their power to induce cravings and their bond with the addictive behavior is lessened. Experiencing this progressive disassociation in a controlled environment also plays a critical role in both recovery and relapse prevention, as it enables the person to strengthen their coping skills and successfully deal with cravings in real-world situations (Lacovino, Gredysa, Altman, & Wilfley, 2012).

There are several alternative options available for those who want to develop a better relationship with food and overcome their tendencies to binge eat. These include cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy and weight loss therapy. In cases where psychotherapy is not effective, medications such as antidepressants or stimulants might also be prescribed.

The Bottom line

BED is about more than food. For mental health experts, it is a complex psychological condition that requires special attention and professional treatment. For Jane and million others alike, it is an everyday battle within the self. If you are concerned that you – or a loved one – may have an eating disorder, consider professional help or reach out to patient organizations for resources and support. Recognizing BED is the first step to recovery. Remember that you’re not alone, and no one is totally exempt from the potential of developing disordered eating patterns. Once you know what your demons are, make a game plan to overcome them. It’s a challenging battle, but it CAN be won!

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Bulik, C. M., Kleiman, S. C., & Yilmaz, Z. (2016). Genetic epidemiology of eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(6), 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000275

Dakanalis, A., Carrà, G., Calogero, R., Fida, R., Clerici, M., Zanetti, M. A., & Riva, G. (2015). The developmental effects of media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes on adolescents’ negative body-feelings, dietary restraint, and binge eating. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(8), 997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0649-1

Goldschmidt, A. B., Engel, S. G., Wonderlich, S. A., Crosby, R. D., Peterson, C. B., Le Grange, D., … Mitchell, J.E. (2012). Momentary affect surrounding loss of control and overeating in obese adults with and without binge eating disorder. Obesity, 20(6), 1206-1211. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.286

Guerdjikova, A. I., Mori, N., Casuto, L. S., & McElroy, S. L. (2017). Binge Eating Disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(2), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.01.003

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P. A., Chiu, W. T., Deitz, A. C., Hudson, J. I., Shahly, V., … Xavier, M. (2013). The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 904–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020

Lacovino, J. M., Gredysa, D. M., Altman, M., & Wilfley, D. E. (2012). Psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0277-8

Mathes, W. F., Brownley, K. A., Mo, X., & Bulik, C. M. (2009). The Biology of Binge Eating. Appetite, 52(3), 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2009.03.005 van den Akker, K., Schyns, G., & Jansen, A. (2018). Learned overeating: Applying principles of pavlovian conditioning to explain and treat overeating. Current Addiction Reports, 5(2), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0207-x

About the author

Freideriki Carmen Mamali (MSc) is a PhD candidate at the Department of Clinical Psychology at University of Amsterdam (NL). Her academic responsibilities include teaching undergraduate classes, supervising thesis students and conducting research in the domains of clinical psychology and experimental psychopathology. The aim of her research work is to identify and further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the relationship between cognitive maladaptive schemas and the manifestation of complex psychopathology, including personality and dissociative disorders.