Students in the Research Master of Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience with a specialization in Psychopathology (RM PP) at Maastricht University (UM) the Netherlands, were invited as members of a fictional advisory committee of the Dutch Health Council consisting of experts in overweight, obesity and eating disorders. Over the course of four weeks and using various sources and assignments (lectures, literature discussions, quizzes, and popular science writing) they had to find out whether national programs to prevent overweight and obesity increase the risk of the development of eating disorders. During a plenary event meeting on March 31st 2022, each student pitched their findings, and students critically discussed what is known from empirical research into the association between the promotion of healthy nutrition, healthy exercise, and loss of overweight on the one hand and the causation of eating disorders on the other hand. Based on this, they formulated a final group advice which can be found below.

Our population size is growing, not just in number but in actual body size. In 2008, more than half the adult population in the Netherlands were overweight, and close to 20% were obese. Even among young children from age 4, the numbers are surprisingly high, with 12.7% overweight and 2.9% obese (WHO, 2013). These numbers have been on the rise for the last decades. The multitude of health problems that emerge as a result of unhealthy weights span from coronary artery disease to depression, with far-reaching consequences: productivity loss, partner and family costs, health care, and more, totalling a cost of 79 billion euros per year in terms of societal impact (Hecker et al., 2022).

It goes without saying that preventing obesity is a priority. However, there is concern that obesity prevention programs may increase the risk of eating disorders. Indeed, obesity and eating disorders share many common risk factors. Research shows that dieting is particularly damaging: students who even moderately restrict their food intake are 5 times more likely to develop an eating disorder. They are also likely to have higher weight and engage in binges (eating uncontrollably and in larger than usual amounts in a short amount of time) more often. A recent clinical report further stresses that parental talk about weight is related to both obesity and eating disorders in adolescents, regardless of whether the parent is talking about their own dieting or encouraging such practices in their child (Golden et al., 2016). Given this link, should we conclude that national programs to prevent overweight and obesity will increase the development of eating disorders? The simple answer is: no, as long as they are done correctly.

Now, what does “done correctly” mean? It means learning from our mistakes and acknowledging the power of how we frame interventions. Current prevention interventions focus too much on weight control and food. If these messages are taken too far, they can have drastic unintended consequences. A study by Lebow and colleagues (2015) found that 37% of teens seeking treatment for an eating disorder had previously been obese – showing that it is entirely possible for a person to move from one side of the weight spectrum to the other. The better and more useful approach is to focus on health promotion, which will allow programs to target overweight and eating disorders simultaneously. A study by Austin and colleagues (2005) provides a good example. Their school-based obesity prevention program was effective both at reducing the incidence of obesity in adolescent girls as well as reducing disordered eating. The programme, Planet Health, focused entirely on promoting healthy nutrition and exercise habits and did not mention weight, dieting, and related constructs. Other potential ways to promote health include the encouragement of intuitive eating rather than self-monitoring, and teaching our citizens about body positivity and media literacy from a young age. This may be useful in counteracting the pervasive “thin ideal” and stigmatization of overweight bodies on social media.

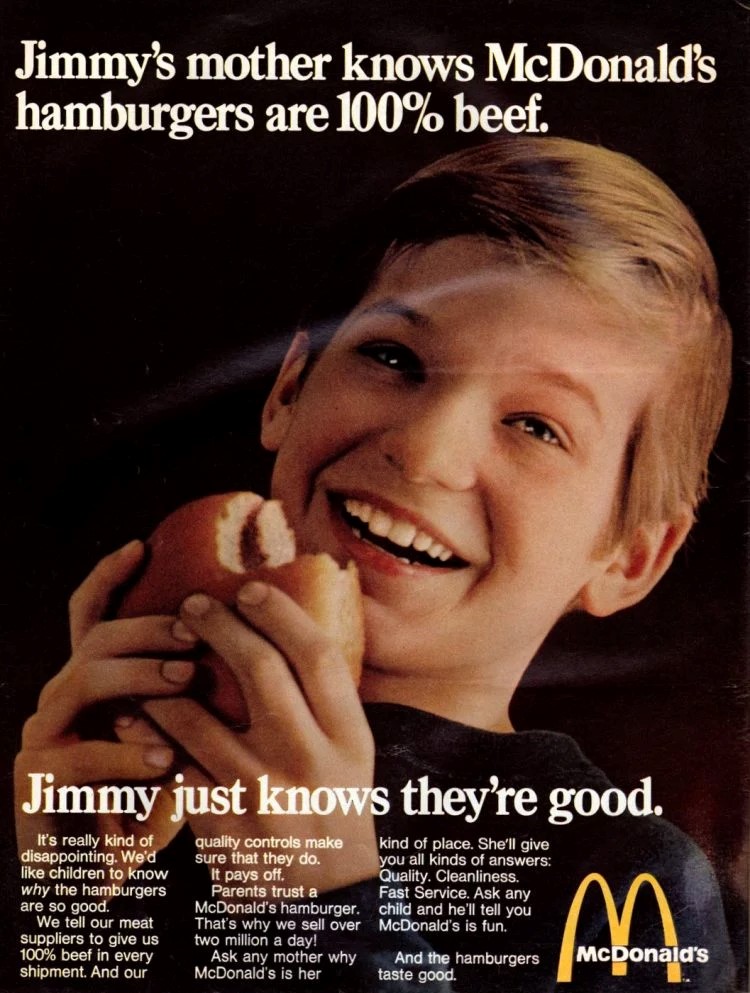

Furthermore, not all responsibility should be put into the hands of the individual. First, research shows that giving individuals the whole responsibility of implementing health behaviors can lead to dangerous perfectionism. For example, health-tracking technology such as fitbits have been associated with dietary restraint and increased concern around eating (Simpson & Mattzeo, 2017). In addition, intervention programmes must acknowledge and mitigate the obesogenic environment we live in – so that making a healthy choice becomes the easier choice – and not a question of formidable will power. To do so, the government should support policies that subsidize health and nourishing foods such as wholegrains, vegetables, fruits, and legumes, tax ultra-processed foods, reduce the availability of junk food, and restrict advertisements. This way, everyone could have access to healthy foods, and parents would no longer be deceived by a McDonalds poster luring them into thinking they are doing something good for their child because they know “McDonald’s hamburgers are 100% beef” (1969).

How may we fund all of this? Our capitalist society works on the principles of efficiency and productivity, and no one can be productive or efficient when they are unable to walk up the five flights of stairs when they get to work, or when they spend most of their days in and out of doctors’ offices. Similarly, employee happiness has been linked to productivity increases (Bellet et al., 2019), but overweight and obesity significantly and negatively impact on happiness (Katsaiti, 2012). Given that productivity losses due to obesity and overweight are even greater than the health-care cost in terms of total societal impact (Hecker et al., 2022), we are convinced that by first putting more money into research and interventions, we will end up in profit by better preventing and managing obesity/overweight and eating disorders at the same time.

In conclusion, it is like Hecker and colleagues (2022) say: “The existing approach of eating less and moving more as the only solution for solving this condition is really outdated and can harm the patient even more” (p.11) – so let’s do better, for ourselves and our children.

On behalf of the student cohort RM PP (2021-2022):

- Alexandra Pali, Instagram: a.lexandraa and Linkedin: www.linkedin.com/in/alexandra-pali-6897811b8.

- Chloé Pronovost-Morgan

- Solana Kenyon, Instagram: solana_kenyon: linkedin.com/in/solana-kenyon-a61230247 .

Under the supervision of Dr. Lotte Lemmens (course coordinator)

References

Austin, S. B., Field, A. E., Wiecha, J., Peterson, K. E., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2005). The Impact of a School-Based Obesity Prevention Trial on Disordered Weight-Control Behaviors in Early Adolescent Girls. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159(3), 225. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.3.225

Bellet, C., de Neve, J. E., & Ward, G. (2019). Does Employee Happiness Have an Impact on Productivity? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3470734

Golden, N. H., Schneider, M., Wood, C., Daniels, S., Abrams, S., Corkins, M., de Ferranti, S., Magge, S. N., Schwarzenberg, S., Braverman, P. K., Adelman, W., Alderman, E. M., Breuner, C. C., Levine, D. A., Marcell, A. V., O’Brien, R., Pont, S., Bolling, C., Cook, S., . . . Slusser, W. (2016). Preventing Obesity and Eating Disorders in Adolescents. Pediatrics, 138(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1649

Hecker, J., Freijer, K., Hiligsmann, M., & Evers, S. M. A. A. (2022). Burden of disease study of overweight and obesity; the societal impact in terms of cost-of-illness and health-related quality of life. BMC Public Health, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12449-2

Katsaiti, M. S. (2012). Obesity and happiness. Applied Economics, 44(31), 4101–4114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.587779

Lebow J, Sim LA, Kransdorf LN. Prevalence of a history of overweight and obesity in adolescents with restrictive eating disorders. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):19–24

Sánchez-Carracedo, D., Neumark-Sztainer, D. & López-Guimerà, G. (2012). Integrated prevention of obesity and eating disorders: barriers, developments and opportunities. Public Health Nutrition, 15(12), 2295–2309. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980012000705

Simpson, C.C., & Mazzeo, S.E. (2017). Calorie counting and fitness tracking technology: Associations with eating disorder symptomatology. Eating behaviors, 26, 89-92.

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (2013). Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity Netherlands. World Health Organization. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/243315/Netherlands-WHO Country-Profile.pdf

1969 McDonalds Hamburgers Vintage ad., Vintage Food Ads. (n.d.). Retrieved June 28, 2022, from https://www.atticpaper.com/proddetail.php?prod=1969-mcdonalds-vintage-ad

About the author

Dr. Sieske Franssen is a cognitive neuroscientist working as a postdoc at Clinical Psychological Science and Cognitive Neuroscience at Maastricht University (NL). Her PhD project focused on the influence of mindset on neural responding (fMRI), physiological responding (hormones and metabolism) and behaviour (e.g. subjective craving and intake) in the context of (over)eating. After her PhD she worked as a postdoc to develop a mobile application with an individually tailored intervention using a network approach to reduce obesity in children. In the Socrates project, Sieske will contribute by designing and executing fMRI studies to examine the influence and effectiveness on neural responses of a VR-based treatment using embodiment for people who are overweight/obese.