‘’The government wants to reduce the number of fast-food restaurants in the city center’’. This was one of the news headlines in the Netherlands on the 18th of March last year. A very experienced liberal would say that this is the downfall of politics in the Netherlands. But what if Mr. van Ooijen, the Secretary of state responsible for this plan, is right? Nowadays, almost around every corner, neon letters are grabbing your attention and demanding you to come inside to order something that has at least enough calories to ensure you won’t have a shortage of them at the end of the day. Moreover, the number of fast-food restaurants has been increasing in the Netherlands in the past five years by 27%. In other words, we are living in an obesogenic environment. An obesogenic environment characterizes itself by having a high availability of unhealthy nutrition possibilities and an increasing occurrence of a sedentary lifestyle: a way of life where people mostly sit or lay during the day with very little to no exercise. Consequently, obesity numbers are increasing. According to the World Health Organization, more than one billion people worldwide are obese and these numbers are still growing.

The main treatment targets are exercise, diet, and behavior modifications. Even though these treatments have some efficacy, this is low: only less than 5% of the people in these treatments lose weight and are able to maintain this weight loss (in a non-surgical program). Therefore, we need to ask ourselves: what kind of intervention is suitable to combat this low-efficacy rate? Before we can answer this question, we must consider what is happening in people who suffer from obesity besides the nutritional and environmental aspects. The allocentric locked hypothesis is a theory that can explain what happens in the mind of obese people. This theory is built on the assumption that our bodily experience has an egocentric (first-person experience) and an allocentric (third-person experience) reference frame. The egocentric one can be best described as the player one view in a video game: the location of objects relative to the body center. Therefore, the primary source of information is related to direct sensory input/stimulation. Furthermore, the allocentric reference frame can be seen as the point of view you have in, for example, PacMan: the space external to the observer is essential, and the position of an object does not change if the observer moves. Moreover, for this reference frame, beliefs, abstract knowledge, and attitudes related to the body are important. According to the allocentric lock hypothesis, obese people have a deficiency in their allocentric reference frame. In other words, it is assumed that, even though obese people will lose a significant amount of weight, this reference frame won’t update to this weight loss. Consequently, the negative image of their body remains and can induce a feeling of hopelessness with potential opposite behavior, binge eating, as a result.

A possible solution to address this locked issue is implementing Virtual Reality (VR). In VR, a 3D environment is recreated. Moreover, due to technological advances, it has a high ecological validity, which means that people feel that they are in that environment for real. In the context of obesity, VR can counteract this allocentric lock by unlocking the negative memory of their own body.

For our research, this is the starting point. First, we want to investigate if VR positively affects the treatment of obesity, and later, we want to elucidate if expected brain regions are active during this VR experiment. The VR task consists of different avatars that differ on multiple factors. These factors entail self or generic avatars, fit or unfit, and current or future avatars. In the end, six conditions will exist whereby all possible avatar combinations are created. During the VR task, the participants will, among others, execute body movements (e.g., squatting, hitting color balls), physio measures, their readiness to change (motivation), and their feeling of body embodiment will be examined. In the end, we expect that the self-avatar will result in a higher readiness to change than the generic avatar. We forecast this effect because we hypothesize that a self-avatar leads to a higher body embodiment and that a higher body embodiment can be a crucial factor in motivation/readiness to change. However, the evidence for this statement is limited, which underlines the importance of our research. Furthermore, we expect that a higher fitness of an avatar affects readiness to change positively. To conclude, we forecast that self-fit avatars lead to a higher motivation to live a healthier lifestyle than the future/current generic unfit avatars do. The second part of our study will have the same approach, but the execution will differ. Namely, the additive value of the second study will be the measurement of the participant’s brain activity during the execution of a VR task. Brain activity measurement will be done with functional resonance imaging (fMRI). This technique measures indirect brain activity by measuring the ratio between oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in a specific brain region. The spatial resolution (the accuracy of detecting brain activity in a particular area) is high in fMRI. But with measuring fMRI you cannot execute body movements in the scanner. Therefore, the body movements like squatting will be replaced by more subtle hand or foot movements. In this fMRI study, we want to confirm the hypothesis that a self-avatar will induce more of a feeling of body ownership than the generic avatar. Therefore, we expect brain regions related to the bodily self to be more active when the self-avatar is shown to the participant.

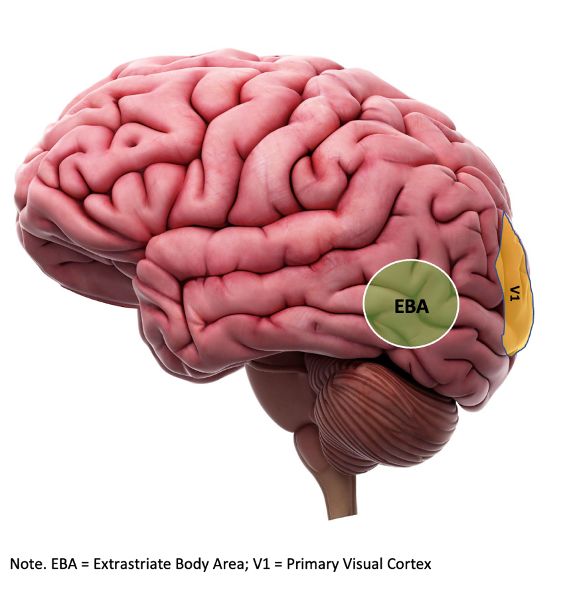

An example of such a brain region is the extrastriate body area (EBA). This brain region is a region that is located near the part of the brain where visual stimuli will be processed first (the primary visual cortex). Furthermore, the EBA converges all body-related information from your multisensory system and is, therefore, known to be a brain region involved in self-processing. This role is also reflected in studies where the EBA was active when participants had to do/imagine movements of their arms.

To conclude, Mr. van Ooijen was right: obesity is a problem that will manifest more and more in the 21st century. Therefore, innovative solutions are required to increase the efficacy rate of the treatment of this disease. VR is such an innovative solution and tries to tackle the mindset of obese people by focusing on the allocentric lock hypothesis. Furthermore, our study will emphasize the importance of body embodiment by adding a self-avatar and by measuring this on a neurological level.

About the author: Simon Depla is a student from Maastricht University. He has a bachelor’s degree in Psychology and a master’s degree in Neuropsychology. Currently, he is doing the Research Master Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience with a specialization in Drug Development and Neurohealth at Maastricht University. His main field of interest lies in psychiatric disorders, synaptic plasticity, ketamine, and ketamine-assisted therapy. Soon he will be an intern at Exeter University and will aid in a project focusing on ketamine as a possible solution for (gambling) addiction.

Further reading:

Arzy, S., Thut, G., Mohr, C., Michel, C. M., & Blanke, O. (2006). Neural Basis of Embodiment: Distinct Contributions of Temporoparietal Junction and Extrastriate Body Area. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(31), 8074-8081. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.0745-06.2006

BoldData: Nederland telt meer fastfoodrestaurants dan restaurants. (n.d.). https://www.derestaurantkrant.nl/bolddata-nederland-telt-meer-fastfoodrestaurants-dan-restaurants

Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J., K. Wiederhold, B., & Riva, G. (2016). Future Directions: How Virtual Reality Can Further Improve the Assessment and Treatment of Eating Disorders and Obesity. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(2), 148-153. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0412

Manzoni, G. M., Cesa, G. L., Bacchetta, M., Castelnuovo, G., Conti, S., Gaggioli, A., Mantovani, F., Molinari, E., Cárdenas-López, G., & Riva, G. (2016). Virtual reality–enhanced cognitive–behavioral therapy for morbid obesity: a randomized controlled study with 1 year follow-up. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(2), 134-140.

NOS. (2022, March 18). Kabinet wil minder fastfoodwinkels in de stad. NOS.nl. https://nos.nl/artikel/2421663-kabinet-wil-minder-fastfoodwinkels-in-de-stad

Obesity Treatment. (n.d.). ucsfhealth.org. https://www.ucsfhealth.org/conditions/obesity/treatment

Over one billion obese people globally, health crisis must be reversed – WHO. (2022, March 7). UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/03/1113312

Riva, G. (2011). The key to unlocking the virtual body: virtual reality in the treatment of obesity and eating disorders. Journal of diabetes science and technology, 5(2), 283-292.

Riva, G., Gaggioli, A., & Dakanalis, A. (2013). From body dissatisfaction to obesity: how virtual reality may improve obesity prevention and treatment in adolescents. In Medicine Meets Virtual Reality 20 (pp. 356-362). IOS Press.