How Scientists Are Using Technology to Help Improve Mental and Physical Health ?

The way our brain thinks about our body is an important topic in the field of cognitive neuroscience [1]. Many of us believe that our physical appearance is fixed and unchangeable. However, scientific experiments have shown that we can feel like we “own” non-human body objects, which suggests that our perception of our body is actually flexible [1-3]. One way this has been studied is through virtual reality (VR) technology, where people can wear a headset and see a virtual body instead of their real one. This can create the illusion that they own the virtual body, and can even affect their physiological and behavioral responses [4-6].

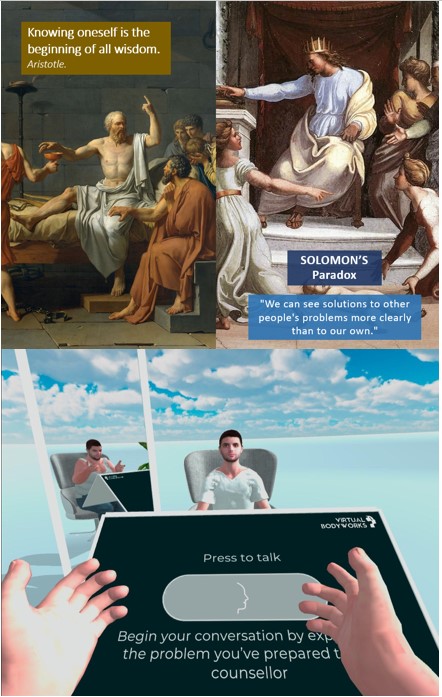

Scientists have been using virtual reality to study how our brains think about our bodies. They can make people see a virtual body instead of their real one and change how it looks, like making it bigger or changing the skin color [7-10]. The researchers found that this can actually affect the way people feel and behave in real life [11-14]. This shows that our brain can be influenced by what we see in virtual reality, and this could be helpful for people who are struggling with their body image or other body-related issues [15-17] (Figure 1).

Using VR, researchers can also study how people give advice to themselves versus to others. Studies have shown that people are often better at giving advice to others than to themselves, which is known as the “Solomon Paradox.” In one study, participants alternated between embodying themselves and the famous psychologist Sigmund Freud in VR [18]. They talked about their personal problems to “Freud” while embodying him, and then gave advice to themselves while embodying their own virtual body. This approach, called the Self-Conversation method, has been found to be more effective than scripted methods for improving perception of progress and help. This paradigm was incorporated into the ConVRself (conversations with oneself in VR) platform [13,19] (Figure 2).

Overall, the use of VR in cognitive neuroscience has potential implications in psychotherapy, rehabilitation, behavioral neuroscience, and consciousness research.

References

- M. Slater and M. v. Sanchez-Vives, “Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality,” Frontiers Robotics AI, vol. 3, no. DEC. 2016. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2016.00074.

- M. Botvinick and J. Cohen, “Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see [8],” Nature, vol. 391, no. 6669. 1998. doi: 10.1038/35784.

- K. C. Armel and V. S. Ramachandran, “Projecting sensations to external objects: Evidence from skin conductance response,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 270, no. 1523, 2003, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2364.

- M. Slater, B. Spanlang, M. v. Sanchez-Vives, and O. Blanke, “First person experience of body transfer in virtual reality,” PLoS ONE, vol. 5, no. 5, 2010, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010564.

- A. Maselli and M. Slater, “The building blocks of the full body ownership illusion,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 7, 2013, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00083.

- M. Slater, “Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 364, no. 1535, 2009, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0138.

- M. Moghimi, R. Stone, P. Rotshtein, and N. Cooke, “The Sense of embodiment in Virtual Reality,” Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, vol. 25, no. 2, 2016, doi: 10.1162/PRES.

- K. Kilteni, J. M. Normand, M. v. Sanchez-Vives, and M. Slater, “Extending body space in immersive virtual reality: A very long arm illusion,” PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no. 7, 2012, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040867.

- D. Banakou, R. Groten, and M. Slater, “Illusory ownership of a virtual child body causes overestimation of object sizes and implicit attitude changes,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 110, no. 31, 2013, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306779110.

- T. C. Peck, S. Seinfeld, S. M. Aglioti, and M. Slater, “Putting yourself in the skin of a black avatar reduces implicit racial bias,” Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 22, no. 3, 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2013.04.016.

- M. Martini, D. Perez-Marcos, and M. v. Sanchez-Vives, “What colour is my arm? Changes in skin colour of an embodied virtual arm modulates pain threshold,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, no. JUL, 2013, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00438.

- D. Banakou, P. D. Hanumanthu, and M. Slater, “Virtual embodiment of white people in a black virtual body leads to a sustained reduction in their implicit racial bias,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 10, no. NOV2016, 2016, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00601.

- S. A. Osimo, R. Pizarro, B. Spanlang, and M. Slater, “Conversations between self and self as Sigmund Freud – A virtual body ownership paradigm for self counselling,” Scientific Reports, vol. 5, 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep13899.

- S. Seinfeld et al., “Offenders become the victim in virtual reality: impact of changing perspective in domestic violence OPEN”, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19987-7.

- M. J. Tarr and W. H. Warren, “Virtual reality in behavioral neuroscience and beyond,” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 5, no. 11s. 2002. doi: 10.1038/nn948.

- M. Martini, “Real, rubber or virtual: The vision of ‘one’s own’ body as a means for pain modulation. A narrative review,” Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 43. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2016.06.005.

- G. Riva, B. K. Wiederhold, and F. Mantovani, “Neuroscience of Virtual Reality: From Virtual Exposure to Embodied Medicine,” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, vol. 22, no. 1, 2019, doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.29099.gri.

- M. Slater et al., “An experimental study of a virtual reality counselling paradigm using embodied self-dialogue,” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, 2019, doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46877-3.

- M. Slater et al., “An experimental study of a virtual reality counselling paradigm using embodied self-dialogue,” Scientific Reports 2019 9:1, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46877-3.

About the author

Elena Álvarez de la Campa Crespo has a PhD in Computational Biology at the Universitat de Barcelona (2019). She is graduated in Biotechnology (2013) and with a Master in Genetics and Genomics (2014). Her doctoral research in the field of computational biomedicine, carried out at Vall d’Hebrón Research Institute (VHIR) and at Centro de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), has revolved around understanding the molecular bases of specific systems and characterizing the impact of genomic sequence variants, with a strong focus on knowledge, determination and computational prediction of protein structures and their molecular modelling. A central axis of her research has been the creation of machine learning models to improve the annotation of genomic sequence variants in sequencing projects, increasing the scope of in silico tools in the clinical environment. All the knowledge gained during her research, a rigorous scientific approach and her first-level analytical and problem-solving skills, have contributed to become part of Virtual Bodyworks. Her role in the company is to be an analyst and data scientist, specialist in Artificial Intelligence, and to manage leading projects in the field, adapted to the creation of Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) applications for medical and social rehabilitation purposes. Both professional careers have endowed her with a great capacity for working on collaborative projects with higher research institutions and also with a considerable experience in grant management, especially European Grants (Horizon 2020, EIT, Interreg-POCTEFA).