“The first step towards getting somewhere

is to decide that you are not going to stay

where you are”.

J.P Morgan

Making lifestyle changes isn’t easy. Even if you have great intentions, you are often not motivated enough to make a change. Maybe you wanted to eat a healthy home-made cereal bowl with granola, milk and fresh fruits, but you didn’t have time to prepare it so you had the same old (ultra-processed) cereals. Or maybe you’d hoped to exercise on a Sunday morning before going for lunch with your friends, but you decided to postpone your plan and sleep more because you were feeling tired.

Sometimes the benefits of our current behaviour outweigh the perceived benefits of a new one. You may know that eating a healthy breakfast or doing more physical exercise would improve your health and quality of life, but sometimes you realize that these lifestyle changes are not as valuable for you as other things in your everyday life. For example, you may say to yourself: “Exercise is just not as valuable for me as my sleep on a Sunday morning” or “Eat a quick already-prepared cereal bowl for breakfast every morning is more important than it is to prepare a healthy cereal bowl because it allows me to go to work early so that I can spend more time with my kids in the afternoon”.

Sometimes you are not ambivalent enough about lifestyle changes. The concept of neural plasticity can help you to understand why some habits are so difficult to change. The brain works and changes based on your experiences. When a habit is well-established, then automatic connections allow your brain to know what is coming next. Already established behaviours occur on an automatic mode and you can enjoy their benefits effortlessly. On the contrary, if you want to establish a new habit, new neural connections have to be created and the old ones have to adjust (or stop functioning). This requires some effort and discomfort at the beginning, but above all, enough ambivalence to carry out a lifestyle change. If you are not ambivalent enough about a specific lifestyle change, nothing can change.

What is ambivalence? According Miller and Rollnick, the inventors of Motivational Interviewing, ambivalence is part of the human nature, “a normal step on the road to change”. It represents a person’s experience of simultaneously feeling two ways about changing his/her behaviour; at the same time willing to make a change and feeling reticent to do so. You can imagine the intense discomfort that one can feel when feeling attracted or pushed in at least two different directions.

It is important to experience ambivalence in a non-judgmental way and be compassionate with yourself. Try to recognize the negative feelings that you may feel while engaging with a new behaviour (i.e. discomfort, uncertainty) and the sense of loss and pain you may experience when modifying or giving up the previous behaviour.

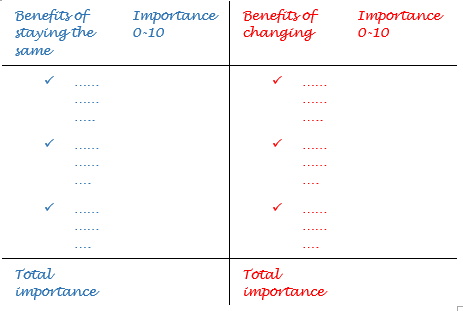

Check your ambivalence by doing a simple exercise: Identify one thing that you’d like to change in your life, making it as specific as possible and draw 2 columns on a piece of paper: On the left side, write down the benefits of staying the same and on the right side, the benefits of changing.

Now look at both columns and try to weight the positive arguments for your current status quo (not changing) and the positive arguments for changing, in line with your own personal values. Weight each argument on a scale from 0 to 10 based on its importance. Now observe if you can start to feel more ambivalent, a little desire to change your current behaviour that might not be so good for you. Feel compassion and understanding for yourself, recognizing that your desire to change may just not be strong enough. If you see that the reasons for not changing outweigh the reasons for changing, don’t feel guilty with yourself. If you feel ambivalent, ambivalence is motivating and motivation facilitates change.

About the author

Dr. Dimitra Anastasiadou is a psychologist and researcher with a PhD in Clinical and Health Psychology (International Mention). She has expertise in the prevention, assessment and psychological treatment of Eating Disorders and Obesity as well as in eHealth interventions. She is currently working as a post-doctoral researcher at the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Research in Barcelona, Spain, and is actively involved in the project SOCRATES being responsible for the coordination and smooth implementation of the Randomised Controlled Trial, which we are going to carry out at the Vall d’Hebron Hospital in the upcoming months.